So I recently came across a really interesting real-life example of how generative AI can fail, especially in the case of using it as a search engine (which, as I’ll explain in more detail, it really shouldn’t ever be used as). I think this example can help highlight the real limitations of this technology and how we must be vigilant when using it (if you must).

A few months ago, my partner and I were in Los Angeles for Christmas. It was his first time there, so when we went to Hollywood to see a show at the Pantages, we spent a bit of time walking around the area to look at the stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. We found lots of notable ones and took a few pictures. I got really excited at one point because I found one that had Kenny Baker’s name on it.

If you are not a Star Wars nerd like me, then maybe this name doesn’t mean much to you, but R2-D2 is my favorite Star Wars character, and he was played by Kenny Baker for many of the movies.

I took a quick pic and we kept walking to get to our dinner reservation. While waiting for our food, I started going through my pictures and posted a couple to my Instagram stories. I was about to post the Kenny Baker one, but something caught my eye that didn’t seem quite right so I decided to wait and double check something.

As you can see in the pic above, each star has an icon on it, that shows what area of entertainment that person was known for. I expected to see a movie camera icon there for Kenny Baker, but as you can see, it is a microphone instead. So that was odd.

I first did a quick search on IMDB to see if there was more than one Kenny Baker. Sure enough, there are quite a few. I then decided to go directly to the Hollywood Walk of Fame’s website and look there to see which Kenny Baker this star is for. As it turns out, it is a star to commemorate the work of an early radio star who performed on the Jack Benny show.

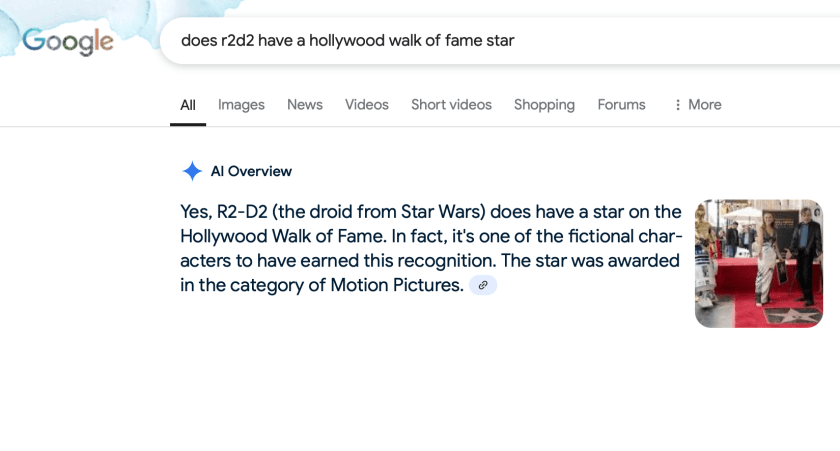

While I was doing this, my partner did a Google search on his phone and asked it if R2-D2 had a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (HWoF). On his phone, an AI-generated result that showed up at the top of the search results to “help” summarize. It clearly said that “Yes, R2-D2 does have a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame” and even provided a nice picture of R2-D2 next to a star.

Unfortunately, this is wrong. And I think it’s wrong in a really interesting way, that can help us understand how this technology works and why it produced this incorrect result. On its face, this result seems plausible. R2-D2 is a beloved movie character from a huge franchise, so it makes sense that he1 (or rather, the person who played him) would have a star. Other people who acted in the Star Wars movies do have stars on the HWoF, including Mark Hamill, Carrie Fisher, and Harrison Ford. And R2-D2 is arguably the most important character in the Star Wars franchise2.

If you click on the link provided in the confident “AI Overview”, it takes you to a Wikipedia page of “fictional characters with stars” on the HWoF. Which R2-D2 is not on.

So, how did this incorrect result happen? Let’s first look at how this kind of technology works. These kinds of summarized results are outputs of generative AI, sometimes abbreviated as genAI. If you’ve heard of ChatGPT, it is one of these. It is based on a large language model (LLM), that has taken in vast amounts of text data, largely (and illegally, in a lot of cases) from internet sources. This includes Wikipedia, Reddit, and other online forums. LLMs take all of this data and then make a model of the likelihood of different words and phrases occurring together. Basically, you can think of it as a big table of numbers. How likely is one word going to follow another? It’s fancy predictive text. So for instance, if I type the word “movie”, there’s a decent chance that the following word is “character”, “plot”, or “screen” but a very low chance that it is “banana” or “easily”.

These LLMs also have information about structure and style. So it can understand that something is in a typical essay format versus a poem. One of the things it is good at is transforming one written genre into another (e.g., turn this paragraph into a Shakespearean sonnet). It can also turn a set of bullet points into a paragraph and vice versa or turn this paragraph into a haiku3.

But it’s also quite bad at a lot of things. And because it has one job, which is to generate text that sounds plausible, it will always do that, even if it’s not sure of the results or if there are no real results to be had. This ends up producing what is sometimes termed “hallucinations” or “slop”, where the LLM will make up things that sound plausible, because that is its job. For instance, if you’re working on an academic paper and you ask it to find some references on a certain topic, it will just make them up sometimes. The journal titles and paper titles will look plausible, but they don’t actually exist.

So, then, back to our R2-D2 example. How did this happen? Especially considering that the correct answer is actually in the source data on Wikipedia. I don’t know for sure, as I (or anyone else not working on these projects at these big tech companies) don’t have access to their models. But I have some ideas about how it decided to give this response. So, first there are a lot of associations between R2-D2 and the HWoF. For instance, there is that image (see above) that shows R2-D2 next to a star. It turns out that that was for the ceremony to celebrate Carrie Fisher’s star on the HWoF. (R2-D2 was also present when Mark Hamill received his star.) The training sets for LLMs include many things, including posts from Reddit, Wikipedia, and other publicly available information on the internet. There are lots of mentions on the internet of other actors from Star Wars being at HWoF events or getting their own stars. And there are of course lots of sentences in the LLM training sets that talk about R2-D2 with other Star Wars characters and actors. There is a Kenny Baker that has a star on the HWoF. And there are lots of sentences connecting (the name) Kenny Baker to R2-D2. And R2-D2 is in the Robot Hall of Fame. So, there is a clear connection. It is plausible.

But again, it is wrong. R2-D2 does not have a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. (And Kenny Baker, the actor who played him, does not either, just to be clear.) Lots and lots of connections make it seem like a plausible answer to the prompt. But it is wrong. LLMs are not doing a search, as we understand it, they are generating a plausible sounding answer.

You should only use this kind of technology if you are a content expert in the area. Otherwise you won’t be able to discern whether or not the information it’s giving is correct. So, this hopefully could help you decide which kinds of uses are appropriate for this technology and which are not. And to remember that that depends on who is using it and what they already know.

In addition to all of the above issues mentioned, it should be noted that LLMs and genAI in general, are also terrible for the environment. They require huge data centers and a large number of calculations to train their models and perform their predictive functions. This takes up an absurd amount of energy and water (to cool down the computers). Some estimates show that it takes 7-8x the amount of energy to run a ChatGPT query as it does to do a Google search. So, please reflect on this before using this technology and think about whether or not it’s worth destroying the planet over.

Remember, LLMs like ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini do not know anything. That is not the task they are performing. They are predicting likely text combinations based on a large corpus of what people have already said. That is all. They can’t do a search and cannot provide factual answers. The only person checking the accuracy of the output is you, the user, so you need to double check all of the information it gives you.